The OSINT bloggers, who have tracked the depletion of Russia’s Soviet-era arsenal of equipment, weapons, or armor, dream of attrition but these mid-summer dreams, apart from being unprecedented non-military objectives, have awoken to a harsh, cold reality. The situation is far more complex than a few knocked artillery pieces, armored personnel carriers, or infantry fighting vehicles. Russia’s army is adapting and it is adapting fast.

OSINT bloggers have tracked a myriad of Russia’s Soviet era of weaponry, equipment or armor. Coupled together with production rates, the rate of Russia’s losses in its old arsenals, they argue, contribute to a situation in which Russia “simply cannot hold out much longer.” These are dreams of attrition. These dreams of attrition are a necessary result of a lack of understanding about a feature of warfare on the eastern front.

Materialschlacht

The word Materialschlacht is the German word for a war of attrition but the term contains much more meaning than its designation. While its designation treats attrition in terms of manpower, the underlying roots of this Kofferwörter relate less to manpower than to matériel.

The battle of Bakhmut-Artemovsk, as one commentator from the Jamestown Foundation noted, “the Battle of Bakhmut as a Materialschlacht (material battle), an approach in which the military command spends available reserves to wear down the enemy, Moscow adopted the tactic of exhausting Ukrainian defensive positions with constant attacks.” The opposite is true. Ukraine expended available reserves in an attempt to wear down the Moscovites but the ‘meat-grinder’ the Russians induced with Surovikin’s withdrawal from Kherson canalized Ukraine’s armed forces away from the Dnipro (which is dangerous for Crimea) towards the north (where the Russians are closer to their border, supply lines, or munitions depots).

The result became the destruction of both Ukrainian manpower as well as matériel that caused Materialschlacht to reverberate throughout the entire Ukrainian armed forces, causing continuous reconstitution throughout its entire ranks, whose brigades could not both train on or be resupplied with depleting stocks of armor (such as the T-64) or munitions (such as the 155mm artillery shell), since Ukraine could not produce either. According to the Texeira leaks, NATO needed to train no less than nine new brigades (many of which have been decimated already in the Donbas) to restore Ukraine’s ability to conduct offense.

Perfanov’s theory is backwards. Despite being backwards, Perfanov’s theory, however, has a much deeper significance for war on the eastern front. Although he does not make any mention of its relation to the eastern front, Materialschlacht is a naturally occurring aspect of its warfare. Indeed, it is actually preceded by the Minard paradox that comes from a much earlier analysis of Napoleon’s 1812 campaign.

Minard Paradox & the Dnipro

The Minard paradox is the situation Napoleon faced in his 1812 campaign against Czar Alexander’s largely foreign advised military force. Kutuzov, Suvorov’s disciple, counseled against a direct engagement for a decisive battle with the French coalition, choosing to withdraw carefully into Russia’s strategic depth. With his withdraw, Napoleon’s logistics became strained, the deeper his Grand Armée pursued, causing his army to disintegrated rapidly. Napoleon’s army disintegrated in more than merely manpower; his army disintegrated completely from control, command, or communication down to supplies, munitions, or heavy weapons.

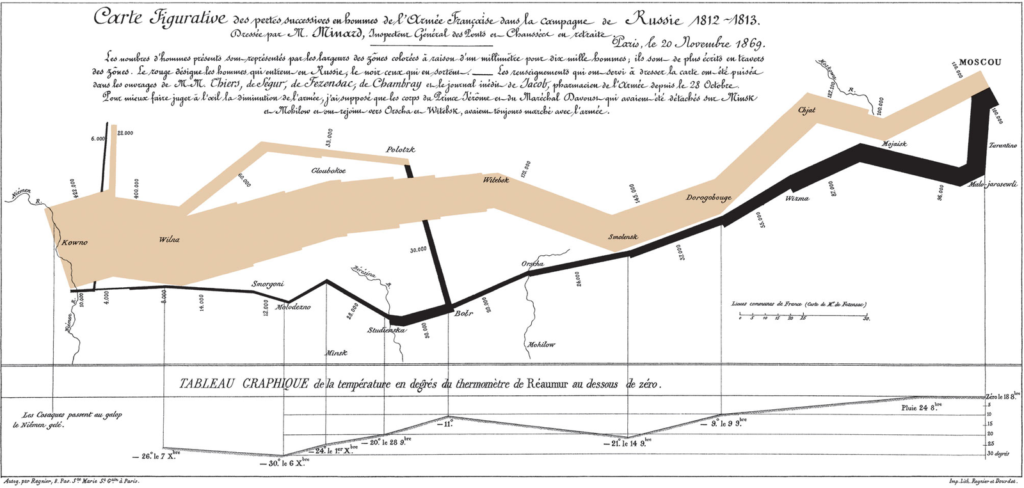

Charles Joseph Minard (27 March 1781 – 24 October 1870), a French civil servant, is famous in the study of Data Science for his creation of colorful, illustrative, scientifically revealing graphs, maps, or diagrams.

Minard is best known for his creation of a famous map on Napoleon’s disastrous losses called “Carte figurative des pertes successives en hommes de l’Armée Française dans la campagne de Russie 1812–1813).” Statistician professor Edward Tufte described Minard’s graphic as what “may well be the best statistical graphic ever drawn.” The map represents six types of data in two dimensions: the number of Napoleon’s troops; distance; temperature; the latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates.

While Minard’s graph mainly deals with losses in French manpower, the remaining losses, which often precede, accompany or follow these losses, may be added easily. It is easy, for instance, to imagine that as the French began to lose its manpower, the oxen Napoleon gathered for the campaign began to die; these provisions for transport as well as for food by necessity became more and more limited; the carriages Napoleon utilized for transport lost horsepower. The loss of carriages Napoleon utilized for transport prevent his army from carrying supplies. Supplies like munitions or cannons came in shorter supply as Napoleon continued his Long Road to Moscow.

This is Minard’s paradox. The strategic depth on the eastern Front, which covers hundreds of thousands of miles, becomes extremely complicated for any opposing force, especially when the Russians entrench. Minard’s paradox applies to any new Surovikin line the Russians seek to establish at the banks of the Dnipro river.

Should the Russians seek to establish a new Surovkin line at the banks of the Dnipro, the Ukrainians would have to overcome Minard’s paradox in terms of Materialschlacht. Since the Ukrainians failed to do so during the 2023 ‘Spring’ counteroffensive, there is no reason to think that the Ukrainians would be able to do so again in 2025 or 2026 against a much more complex Surovikin line pitched against the Dnipro.

Clausewitz, Clausewitz, Clausewitz

The Ukraine has not been able to match its war strategy with its policy. In the attempt to isolate Crimea with a thousand cuts, the Ukrainians have shifted focus away from taking control over the Black Sea to degrading Russia. In its most recent strike on an oil facility, which is still burning after more than four days, Ukraine has not widen the scope of its control over the Black Sea. While the initial strategy sought “to make Crimea untenable” for the Russians, the shift towards degradation comes after more than a year of pitched sea battles.

These pitched sea battles initially succeeded in the destruction of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet; a consequence of these attacks became Russia’s decision to transfer the location of its dock from the Black Sea to Novorossiysk, from Ukraine to Russia. Russia, however, adapted its defense, building both Flaktürme (large, above-ground, anti-aircraft gun blockhouse towers with immobilized Pantsir-2 systems) as well as developing a new strategy for combating naval kamikaze drones. These innovations results in an entirely new situation on the Black Sea.

Russia supplemented these innovations in naval power with long range strikes on ships, ports, or weapons depots together with a concerted effort to undermine local military efforts with partisans in Odessa. Russia’s strategy, which has been aimed at maintaining its majority control over the Black Sea, matches its policy to preserve the military power of the Crimean peninsula, despite different, continued Ukrainian attacks. Russia’s supplemented military plans match its policy.

Ukraine’s decision to shift away from a strategy for an ‘untenable Crimea’ to a degradation of Russia has necessarily failed by a factor of its own immeasurability. In ancient Greece, one of the most notable pre-historic philosophers, Protagoras said: “πάντων χρημάτων μέτρον ἐστὶν ἄνθρωπος.” In Ukraine, the Ukrainians are the measure of everything but have measured nothing. The measure of degradation for an oil depot, for instance, has never been calculated to a unit of degradation for which the sum of the units equal the untenability or destruction of an aspect of Russian military power. These attacks are truly willy-nilly. In the absence of any measure, the strategy becomes vacuous. A vacuous strategy can never match a policy.

In a confirmation of Russia’s restoration of maneuver warfare, the New York Times described how Russia is currently seeking to lay siege to Russian villages on the flanks in the Pokrovsk direction. “To the southwest of Toretsk,” the Times writes, “Russian forces are widening a bulge they have cut into Ukrainian defenses, as they push toward the strategic city of Pokrovsk, a railway and road junction.” Rather than attack Pokrovsk directly, which is heavily fortified with trenches as well as anti-tank ditches, the Times observes that “Russian troops are trying to flank [Pokrovsk] by seizing less fortified territory to the south.” According to the Times, Russians “through weak points in Ukrainian defenses, [capturing] narrow strips of land to form pincers around Ukrainian positions before tightening the noose.” Of Selydove, the Times claims “Russian troops have now partly succeeded in forming a semicircle around” the village. Of Vuhledar, the Times claims the village “fell last week after being caught in a pincer movement.”[1]

In regards to Russia’s restoration of maneuver warfare on the steppes of the southeastern Donbas, Russia has began to shift the weight of its integrated arms in different ways to facilitate encirclements. In the so-called ‘ballerina’ cauldron (i.e., кольцo между Невельском и рекой “Волчья”), the Russians have recently reduced targeting with artillery from an established position of fire control along the geographic heights above the Ground Lines of Communication (i.e., GLOCs) leading to the surrounded village of Kurakhove. In response to the reduction in artillery, the Russians have increased dramatically the number of FPV drone attacks, targeting columns, convoys, escorts, or rotations in an effort to seal the encirclement. During Military Summary’s daily update, the host explains how the Russians have applied more weight to FPV drones than artillery or glide bombs to stop traffic from flowing in or out of the encircled village.[2]

References

[1] – [10:43 to 14:51: https://x.com/MilitarySummary/status/1843353883269103643, October 7th, 2024]

[2] – [On A10: “Russian forces close in on crucial towns in Ukraine’s East,” New York Times, October 9th, 2024]

[3] – [“Why Russia Is in More Trouble Than It Looks,” New York Magazine, October 8th, 2024]

[5] – [“Russia’s Artillery War in Ukraine: Challenges and Innovations,” Forbes, July 17th, 2024]

Russia has staggering amounts of artillery, both in the field and in reserve.

A February 2024 report from RUSI estimated that Russia had just under 5,000 artillery pieces in the field, of which about 1,000 are self-propelled guns on tracked vehicles, the rest being old-fashioned towed artillery.

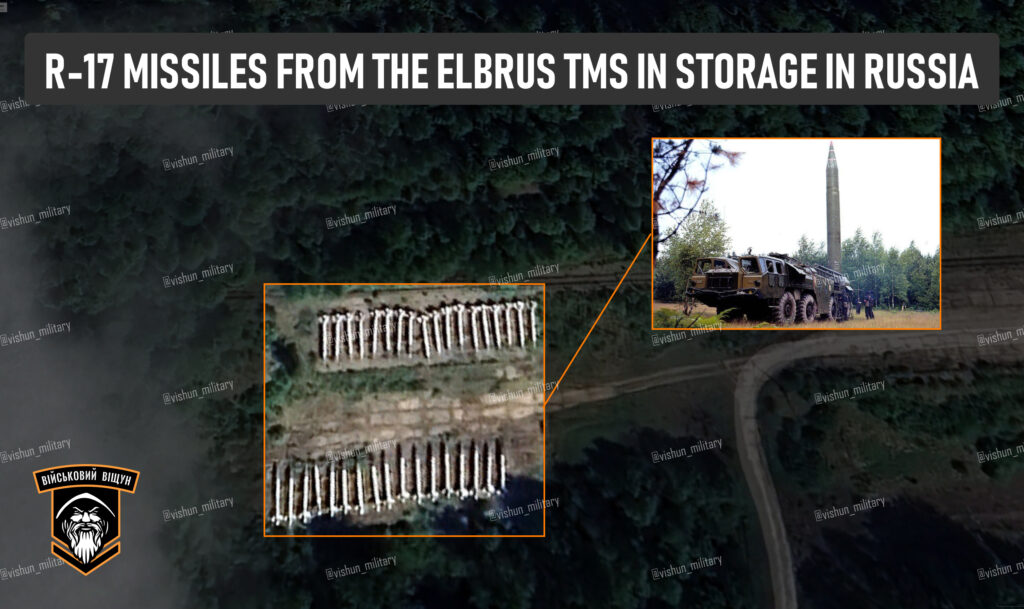

Several OSINT analysts have worked at assessing exactly how much Russian equipment remains in these storage sites, how much has been removed and how much of the remainder is still usable.

HighMarsed has published some of the most detailed analysis, going through site-by-site and trying to identify every single piece of equipment at every storage location. This work, along with the results published by CovertCabal and others, is widely quoted in defense circles as the best evidence of Russia’s remaining capacity.

[5] – [“Russia’s Artillery War in Ukraine: Challenges and Innovations,” RUSI, August 9th, 2024]

[4] – [“Ore to Ordnance: Disrupting Russia’s Artillery Supply Chains,” RUSI, October 10th, 2024]