Prior to the outbreak of hostilities in the Ukraine, Russia’s import market for foreign vehicles focused almost exclusively on European brands. These brands, such as Kia (i.e., South Korean), Hyundai (i.e., South Korean), Renault (French), Skoda (Czech), Volkswagen (German), Toyota (Japanese), Nissan ( Japanese), BMW (German), and Mercedes-Benz (German), supplied the vast majority of vehicles for Russian consumers prior to the sanctions program the United States continues to impose. The sanctions program, which is a part of the International Sanctions Program (henceforth ISP), is at its 12th package with the European Union ratifying its the package.

After the imposition of sanctions Russia’s imports of foreign vehicles went from 120,000 in the month of October 2021 to nearly 20,000 in May 2022, a rapid decrease. Russia, however, rebounded quickly, substituting European vehicles for Chinese ones. The result has been a surge in Chinese exports to Russia, an unintended affect for the ISP.

In a recently article published by the Wall Street Journal entitled “China Surges to Top in Car Exports,” the authors discuss these rising Chinese exports. The authors mention how “Chinese carmakers seized the void left in the country by the departure of Western carmakers following the war in Ukraine, selling at least five times as many vehicles than the 160,000 it sold in 2022, according to the Chinese Passenger Car Association.” [1] By “void,” the authors most certainly something other than a sudden, inexplicable, rise in the Russian demand for Chinese imports.

Stating as though the result of a ‘free market’ policy of intense competition, the Journal writes: “The rise of China as the center of the world’s automaking industry represents a hardwon victory for Beijing’s industrial policies, after similar achievements.” Of all things the Journal mentions solar panels, as though Chinese production of solar panel has had an impact on the global market.

In the case of Russia, however, Beijing’s “hard-won victory” for its industrial policies, arose more from opportunity than effort. The authors of the article, for instance, make no mention of the void’s origin, where it came from or how it came about in the aftermath of the Ukraine war. The articles make no mention of the ISP, let alone its affect on Chinese goods. Perhaps more importantly the article completely fails to make any mention of the trade routes on which these goods travelled from China to Russia.

China’s increased import of vehicles arose primarily from two important factors; the first is the ‘blowback’ from the ISP; although the ISP sought to undermine Russia’s ability to expand its economy through the closure of its automating industry.

The opposite occurred. Lada, which is the largest manufacture of Russian vehicles, remained in its position, as Russia increased imports from China to compensate for the sudden disruption to productivity resulting from the exodus of domestic automakers, complying with the ISP.

The result became a significant increase in the number of Chinese imports to Russia. Showrooms in Russia, for instance, merely changed signs. A showroom from Moscow, for instance, once belonging to Japan’s Nissan in 2021 suddenly became a dealership for Kaiyi in 2023. Similar events occurred with Russia’s assembly lines.

Secondly, a 360 degree improvement in Sino-Russian relations, centering primarily on the expansion of trade routes, continues to evolve as a result of the Ukraine war. A direct result of this improvement is the activation of the first major railing connecting Russia to China. In particular, the railways Russia constructed together with China in Inner Mongolia have facilitated Chinese imports into Russia.

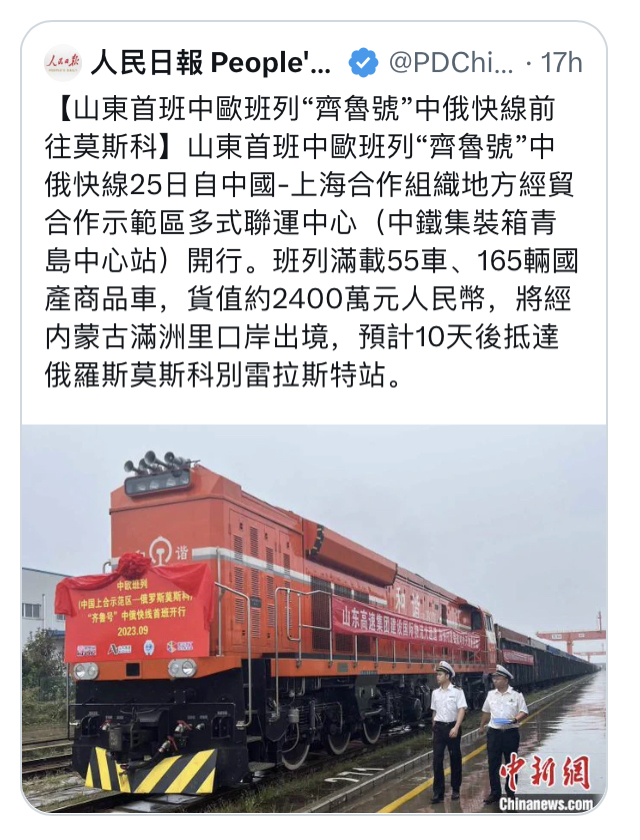

In an article published on People’s Daily China, the authors note that Shandong’s first China-Europe freight train called “Qilu” traveled from Shangdong to Russia on the Beijing-Moscow line. The article noted how the train was fully loaded with “55 vehicles and 165 domestically produced commercial vehicles with a value of about 24 million yuan.” Leaving the country through the Manzhouli Port in Inner Mongolia and expected to arrive at Berelast Station in Moscow, Russia, the freight train “Qilu”reached its destination in ten days.

The Journal makes no mention of the Shandong railway, even though the article discusses how Russia “is estimated to have accounted for around 800,000 of the 2 million more vehicles China exported last year.” While the number of vehicles on the freight train “Qilu” appears to have been less than 200, a faction of the 800 thousand imported Chinese vehicles, the expansion of the Sino-Russian railways point to a new development of the Eurasian continent, connecting these two countries in an unprecedented way. The shipment of Chinese imports is expected to increase as the ISP continues to impose restrictions on the return of European vehicles, just as that of Chinese vehicles is expected to increase along the new railways.

[1] – [“China Surges to Top in Car Exports,” Wall Street Journal, January 10th, 2024